Spawn of Mars

Blog of Fictioneer David Skinner

Frodo's AdventureGetting the Extended Edition of the Movie Trilogy

Tuesday, July 5, 2022 1:12 am

I never got more than a few pages into The Lord of the Rings. I thought the movies were, in the end, boring. Over the years I have acquired a lot of cultural knowledge about Tolkien's intent and craft and, thus intrigued, I have always wished his work would simply attract me, if only so I wasn't the odd man out among my fellow odd men out.

Well, I'm still not planning on reading the book, but on a whim I bought the extended edition of the movie trilogy, and... it's not boring. It may be an unremarkable thing to say, but Lord of the Rings needed the miniseries feel of the extended films. Even though I had never read the books, the theatrical versions had seemed a collection of steps, of scenes, of highlights from something greater.

Now, I have no idea if the extended versions truly represent the books better (aye, there's still no Tom Bombadil, haha), but they at least represent the movies better. There is an epic feel at last, and somehow the human (hobbit, elf, whatever) moments are better grounded.

How to Tell If Your Story Is WokeTry This One Simple Test!

Thursday, July 22, 2021 10:46 pm

Beware! Colossal spoilers for "Black Sails." Among the many irritating traits of the SJW is

obtuseness. She really doesn't understand your objections to her antics. She believes that all she is doing is

providing representation to the Blessed Marginalized. Her face shrunken in petulance, she shrieks: "I'm just putting a gay man in this TV show! What do you have against gays, you hateful homophobe?"

Well, against their behavior, my dear, a few things; but that is not the issue.

I have no objection to the fictional depiction of a man who is attracted to men. I have no objection even to the sympathetic depiction of such a man. Such men exist, such men are human, such men are fodder for literature.

What I object to is your haranguing me on their behalf. What I object to is your sour attempt to disseminate the moralistic shibboleths of your ilk.

Consider the TV show Black Sails.

I love this show. Yeah, whatever, I have my complaints about it; but not one of my complaints is that the central motive of the central character is his love for another man. Indeed, I would argue that Black Sails is so well written, so humanly written, that I would not even want the writers to have done otherwise.

I wish, however, that they hadn't been woke.

Note I am about to make a distinction between telling a tale about a homosexual and being woke. This is what the SJW cannot fathom: That there is a distinction.

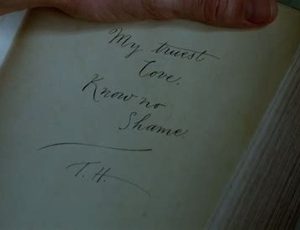

There is a book that was given by Thomas Hamilton to Captain Flint. Hamilton and Flint were lovers. Flint's piratical rage was born from the fatal mistreatment of Hamilton. The book is an important prop in the narrative.

There is an inscription in the book. Here it is.

The name of him to whom this love is directed is, as you can see, obscured; earlier, the viewer supposes it says "Miranda," the name of Hamilton's (public) wife, but in fact it says "James," Flint's true first name.

This inscription is a great example of intrusive wokeness.

If it had said only, "James, My truest love, T.H.", it would have been powerful. With that line, "Know no shame," it becomes propaganda. We hear in it all the bleating about pride and escaping closets; we see the fingers wagging at us — we who might shame the homosexual — telling us to eat our unbigoted spinach.

This is not the only woke moment in the show. The "shame" motif comes up several times. But this example is so stark and compact! One little line. Keep it, and the moment is woke. Remove it, and the moment is human.

Which do you prefer?

P.S. Yes, the very fact that they made Flint a homosexual at all is rather typical of woke approaches to fiction. It's the usual erasure of the hetero. I think we can be confident that Robert Louis Stevenson did not imagine Flint that way. Still, it's a fair change, considering Black Sails only toys with Treasure Island. And it is merited by the good narrative use made of it.

P.P.S. Huh. With that attitude, I should probably return my membership card for the He-Man Poofter-Haters Club.

Derivative of Nictzin DyalhisWriting Another Chronicle of the Venhezian Heroes

Monday, May 4, 2020 10:11 pm

Somehow I became aware of

The Sapphire Goddess: The Fantasies of Nictzin Dyalhis, a collection published by DMR Books in 2018. It collects all the fantasy stories of the unprolific Nictzin Dyalhis, who wrote primarily for

Weird Tales between 1925 and 1940.

Two of Dyalhis's contributions to

Weird Tales are science fiction:

When the Green Star Waned (April 1925) and its sequel

The Oath of Hul Jok (September 1928).

I really liked both of these stories — so much so, that I have written a derivative work. Since Dyalhis's stories are in the public domain, I am free to have my story published, and I hope that Cirsova Magazine will accept it when submissions re-open later this year.

There's an earnestness to Dyalhis's two stories. They are all superlatives, exclamation points, and outsized drama. The seven friends are the very best of their kind: the greatest scientist, the greatest diplomat, the greatest warrior, the greatest cultural scholar, the greatest biologist, the greatest reader of minds, and the greatest... well, the narrator is not presented as the "greatest" chronicler and poet, but he is part of the amazing circle.

The stories are clearly science fiction written before World War II. There isn't a lot of hard science. Nor is there magic; but there is an easy and intriguing occultism. Evil is as much a force as electricity. The technology has that alluring mechanical flavor, free of the atomic and the cybernetic.

The setting is the Planetary Chain, an alternative Solar System. Maybe it's the far future of our own but it seems much more a different place. The names of the planets are just a little off — Venhez for Venus, Jopitar for Jupiter, and so on. There are invocations of Our Lady of Venhez, a being who is not really Aphrodite. Venhez is a planet of love and its sign is the Looped Cross (i.e., ), but everything is sideways of our reality and mythology.

And that was my first handhold in creating my derivative work. Dyalhis doesn't develop things deeply. The world-building, though neat, is mostly suggestive.

My second handhold was the sketchiness of the characters. Hul Jok the warrior is vivid, Vir Dax the biologist has some color, Lan Apo the mind-reader is not a blank, and Hak Iri the poet, if only because he is our melodramatic narrator, is not one-dimensional, but by and large the characters are just carriers of superpowers. As you revel in Hul Jok you lament the general blandness of the others.

So there is a lot of foundation in the two stories but not a lot of definition. There's also an enjoyable spirit (and the touch of an outlook rather removed from 2020). The past century has not exactly produced a communal literary expansion of Hak Iri's Friends & the Planetary Chain. I may even be a pioneer. In any event, I had cause to continue Dyahlis's work; and therefore I did.

No, I did not write a gritty reboot. I'm not out to subvert expectations. Vir Dax does not have a gruesome past with a missing call-girl and Lan Apo is not struggling as a transgendered pansexual. My story is not a parody or even an affectionately comedic re-imagining. I simply wrote the third in a series.

Obviously I am not Dyalhis. Yet there is a manner to his writing that accords with my own and I don't need to mimic him wholly to evoke him. My goal was not, in any event, to don a Dyalhis mask. My work is truly derivative, neither identical nor separate. It follows well, I think.

Now I just need Cirsova to accept it — so that you can read it! Sadly, even in the best case, it won't be published for a year or more. But keep an eye out for The Impossible Footprint.

P.S. "Nictzin Dyalhis," though nom-de-plumey, was the man's actual name, near as can be determined. And I do recommend the collection from DMR.

P.P.S. The Impossible Footprint was eventually published by Cirsova and is also available in my collection Stellar Stories Vol. 2.

My Pulp-Action RecipeWriting Action & Adventure

Saturday, January 18, 2020 3:11 pm

This past week I finished writing

An Uncommon Day at the Lake, a Hamlin Becker tale that I hope to sell to StoryHack.

StoryHack is, as it calls itself, a magazine of "Action & Adventure." This means no tales of navel-gazing and nihilism and ponderous puffery. It also means tales generally free of current-year correctness, a thing that hates fun and other natural human ways of being and is hardly interested in action and adventure.

Obviously, if I want to get into StoryHack, I need to write stories a certain way — the way of the pulps, as it turns out. The editor of StoryHack has himself invoked the Lester Dent Formula, which anyone seeking the Way of the Pulps will eventually discover.

Dent's formula has indeed guided me through my three Becker tales. However, it is truly a formula and, to be frank, it is hard for me to obey. I am not a hack; and I don't say that snobbishly. I sometimes wish I were. I'd love to be able to crank out formulaic tales that make readers happy.

What has happened instead is that I obey a less-rigid recipe. Dent's ideas are at the center, but I have added a few other ideas about successful pulp.

David Skinner's Pulp-Action Recipe

Begin with a mystery (or a menace). Proceed through several twists (ideally three, no less than two). Reach a revelation. End with an epilogue that winds down to a warm, though not necessarily happy, feeling.

The twists should deepen the primary mystery (or menace) or introduce relevant sub-mysteries (or sub-menaces). A mix of mysteries and menaces is usually best.

The action should be continuous (events are not separated by too much time) and physical (actual fights and danger punctuate the twists). Things must worsen as the tale progresses. Obstacles should arise.

Focus throughout on a hero. Whatever his misfortunes, he is not a billiard ball but an agent. Most importantly, though luck and nature can play a role, the hero prevails through his own efforts, leadership, or both.

Remember that men are men and women are women. Don't neglect the romance!

Finally, the tale need not be white hats versus black, but remember that good and evil are real and not merely different points of view. Good may not be spotless but evil cannot win in the end.

And that's it. As I said, very Dentish but not a formula. It has shaped my tales of Hamlin Becker. It's gotten me into StoryHack twice — and soon, I'm hoping, thrice.

P.S. By the way, StoryHack #5 is out. I don't have anything in that issue. Becker #2 will be coming in StoryHack #6, probably in March. Becker #1 is in StoryHack #1.

In Which I Criticize the Great Stanislaw LemJust to Set the Internet Straight

Thursday, August 8, 2019 11:03 am

At least two people on the internet — let's call them Bob and Ted — have been dissuaded from reading Stanislaw Lem. That is a shame; not least because, as usually happens on the internet, they are reacting to something that isn't true.

It began with a list of the best literary SF books. Lem's Solaris is on that list, and the listmaker — let's call him Harry — said this:Lem's humans are some of the best in science fiction as well: they screw up, are late, fail to see the whole picture, act irrationally, and even the brightest of them can be swayed by vanity and pride.

To Bob, this quote is asserting that the best-written character is one who fails — indeed, that humanity itself equals failure; and who wants to read such misanthropy? To Ted, this quote is praising the irrational screw-up rather than the flawed yet ultimately competent character; and who wants to read about incompetent characters?

I'm not about to tell Bob and Ted that Lem is actually imbued with a cheerful vision or that his characters are badass heroes; because he isn't and they aren't. I suspect that Bob and Ted might dislike Lem even if they judged him by actually reading him. But it is unjust that Bob and Ted now have a distaste for Lem because of what Harry said.

You see, Harry is wrong. To say that Lem has the best humans in science fiction is to say that Frosted Flakes have the best jalapeños in breakfast cereals. There are no humans in Lem's books. There are barely any characters.

I've been reading Lem for over thirty years. I have read Solaris four or five times. I love Stanislaw Lem. But honestly, there is no denying the lack of characters in his work.

While it is true that one can point to Ijon Tichy, Pirx the Pilot, or the robots Trurl and Klapauscius, and one could say that each is distinctive, ultimately each is just a character type meant to sustain the type of story he appears in: SF comedy, SF adventure, or robot fable. Indeed, when someone like Tichy ends up in a non-comic tale, it becomes even clearer how merely flexible each character is: an appropriate Protagonist with, at most, a pinch of flavor.

This is especially true in Lem's serious novels. Not one of his characters is memorable as a person. I admit this has always disappointed me. Notably I consider Solaris so good because, rarely among his works, it utilizes actual human emotions. Another of his very best stories — The Mask, about a robot assassin who falls in love with her target — is best precisely because it engages one's sympathy (and has one of the best final sentences ever). But most of the time Lem doesn't care about people, nor emotions qua emotions. His concerns are philosophical; cosmic. His interest is in the man as an atom of mankind, not in the man as a fellow soul.

So does that make his work deficient? Dry? Dull? Not often. He writes wonderfully and sets your mind a-thinking. His robot fables are damn delightful. But, contra Harry, you will never find irrational screw-ups nor the proud and the vain in Lem's dramatis personae. Harry's statement asserts too much. What you will find in Lem is irrationality, screwing-up, pride, and vanity: that is, human weaknesses all but disembodied. A character in Lem is playing a fairy-tale role, at best demonstrating an aspect of human behavior, contributing to Lem's exposition of the cruel mysteries of the universe. Lem's characters are vessels with nametags.

You will find a Snow White in Lem, but never a Falstaff.

In the end I agree with Bob and Ted that Harry is wrong about the "best" humans. It is a pernicious lie that humans are most human when they fail. That is the self-serving excuse for sin, after all. But as I have tried to point out, Harry is wrong about Lem as well. In no sense does Lem contain the best "humans" in science fiction. So ignore Harry.

But read Lem. Yes, you may have to be selective, since at times he can get so philosophical the fiction disappears. Seek anything with Tichy, Pirx, or robots; read the novels Solaris, Eden, Fiasco, Peace on Earth, and above all His Master's Voice; and just be ready to focus on those nametags, because the characters won't really stand out otherwise.

P.S. Lem also wrote excellent reviews of, and introductions to, non-existent books and treatises; but of course these are even more removed from character-rich fiction.

The Glad GameGive Pollyanna Her Due

Thursday, August 9, 2018 3:02 pm

In the midst of an article about something I've forgotten, I came across this, which, because it irked me, I copied down:

Many of us, myself included, preach optimism, positive thinking, and looking at the glass as half full. However, there's a difference between that and being a Pollyanna who looks at the world through rose-colored glasses.

Ah, poor Pollyanna. She is one of those literary characters who, having become an allusion, has ceased being her actual self. I, too, once reductively thought of Pollyanna as a person imperviously deluded about the goodness of the world. Then I read the book.

Somehow or another, Amazon recommended Pollyanna to me. I think it's because I had recently been searching for Cicely Mary Barker coloring books. Anyhow, I suppose I was in some sort of lightened mood, because I agreed with Amazon and bought and read Pollyanna. I really enjoyed it, not least because Pollyanna is the farthest thing from deluded.

Her attitude is supported by what she calls "the glad game." It is a game that her father taught her, and its point is simple: To find something in everything to be glad about. He first taught it to her when she was expecting a doll from a missionary barrel that, in fact, contained only crutches. This saddened her; so her father told her to be glad for the crutches — glad because she didn't need them.

This can seem like the vapid comfort one is usually given upon misfortune: "At least you have your health!" But it is better than that, for the glad game is primarily finding some good in the misfortune itself, not merely in some unrelated thing that can then be construed as compensation.

An example is when Nancy, servant to Pollyanna's aunt, relates how she hates Monday mornings; and Pollyanna says, "Well, anyhow, Nancy, I should think you could be gladder on Monday mornin' than on any other day in the week, because 'twould be a whole week before you'd have another one!"

A perfect example is when Dr. Chilton is lamenting the difficulties of his rounds. Pollyanna timidly notes that being a doctor is the very gladdest kind of business. "Gladdest!" he cries. "When I see so much suffering always, everywhere I go?" And she replies: "I know; but you’re helping it — don't you see? — and you’re glad to help it! And so that makes you the gladdest of any of us, all the time."

According to Pollyanna, there is something about everything that you can be glad about, if, as she says, "you keep hunting long enough to find it." Yes, she realizes perfectly — without any self-delusion or rose-colored glasses — that the glad game can be an effort. But the effort must be made. And why? Because of the "rejoicing texts."

Her father, a minister, had noticed the prevalence of Biblical texts that call for rejoicing. Be glad in the Lord! Shout for joy! He counted eight hundred of them. He told Pollyanna that "if God took the trouble to tell us eight hundred times to be glad and rejoice, He must want us to do it — some."

Pollyanna is not some empty-headed dolt, a comic manifestation of obliviousness, a Candide in a red-checked dress and straw hat. Pollyanna deliberately plays the glad game and is made happy. And in the course of the novel, she brings everyone to the gladness in their lives that they each had been overlooking.

P.S. Amusingly, in a post decrying a reductive allusion, I may have made one of my own! I haven't read Candide in 30 years. I'll let my allusion stand, however.

No, Not That Kind of PulpHere's the Kind I Mean

Tuesday, November 21, 2017 10:53 am

Old pulp has a reputation as vulgar, trashy, lurid, and low; and in their apologetics, the proponents of new pulp are usually quite aware of that reputation.

Sometimes the apology is an outright

apology. Some proponents, for example, explicitly disavow the "racism" and "misogyny" of old pulp. Well, okay. I'm not here to hate races or women, either. But declaring against "racism" and "misogyny" is a concession to the very Stalinist conformity that has been destroying our fiction. Those words are no longer reasonable; the enemy has defined them. These days, putting a woman in a dress and saying she is not the same thing as a man is considered "misogyny." Virtue signaling is not the path to better fiction.

But generally the apology is an affirmation. It is not trying to stay in the good graces of the modern zeitgeist but simply reminding people of the excellence to be found in old pulp; an excellence that is grounded in the pulp style.

Even so, there was something a bit vulgar about pulp. Consider the extent to which the Good People of the time sought to suppress pulp as injurious to morals. The Good People had a point. Scantily-dressed women and salivating killers are not precisely sublime.

But two things can be said.

First, there is a sense in which some vulgarities are better than others. George Orwell, in considering the naughty postcards of Donald McGill, noted that the cards, though obscene and (in Orwell's view) rebellious, were only funny because they presumed a stable society of indissoluble marriage, family loyalty, and the like. I myself have noted that pulp presumes the natural order. So long as the salivating killer is the villain and is so precisely because he is salivating and a killer, morals are not necessarily injured.

Second, even if one were to concede that a lot of old pulp was total trash and beyond redemption, there's still a lot that wasn't. As I read it, the Pulp Revolution has never been about total reversion to the past. It idealizes pulp. And ideals are not bad. Every revolution idealizes. A revolution is only guaranteed to be bad when its ideals despise the past. One can embrace old pulp and still set aside the vulgarity; for it is rather the wonder and excitement that guide new pulp.